At the Danube's mouth, in Romanian territory, lives a Lipovan community from the Russia of centuries ago, surviving in surroundings and circumstances that make their lives seem less like a page from history than one from a tale of Pushkin. My first glimpse of the Old Russia existing outside the boundaries of the new Soviet State had been caught as I cycled in Galicia, the Carpathians, and Bucovina, where the Ukrainian farmers wear their hair cut "under the bowl,'' own their little plots of land, and are devoted to their religion as in the heyday of Tsarism.

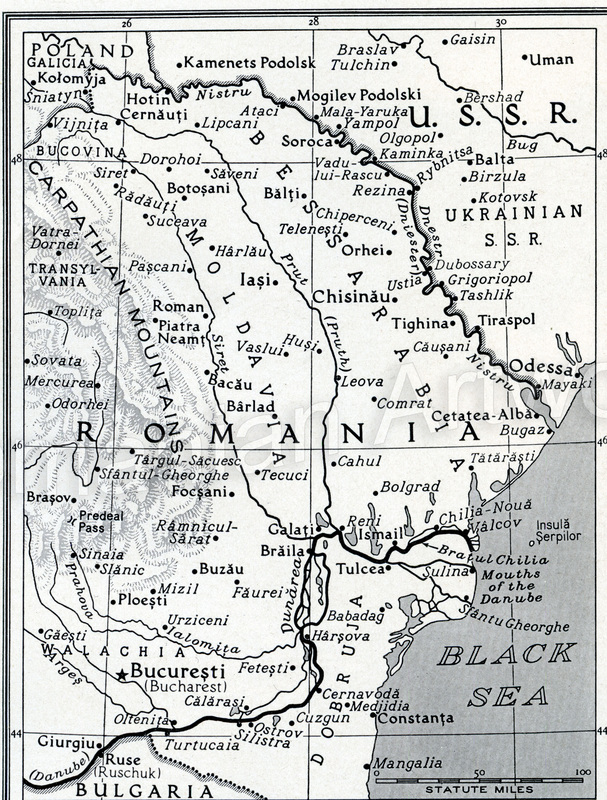

Now in Bucharest I had heard of the vast and mysterious land of the Danube Delta, and when spring came I procured from the military authorities the necessary special permit to pass through the Delta zone to Valcov in Bessarabia on the Black Sea. But my bicycle, on which I had pedaled from Krakow all the way through Poland and Romania, had to be left behind: there are no railways nor, at the time of my visit, were there any feasible roads in the Delta; and so my destination could best be reached by water.

On the "Romania Mare", which I boarded at Oltenita, I met Sergei Nicholaivich, a Valcov Russian. Silistra fell behind us ; then the big railway bridge at Cernavoda, the only bridge to cross the Danube in its lower stretches. Here the sea is only 30 miles away and a canal has long been under consideration, for the river, instead of following its logical outlet, makes a sudden turn to the north and wanders on for more than 200 miles. Vivid scenes succeeded each other: the river traffic, the little ports, the wide brown reach of water, the green marshlands.

After passing a few fields of grain and a rare herd of cows wading under willows growing in the water out from the muddy shore, the Romania Mare came into Galati. Romanian, German, and Greek boats lay at the docks loading lumber and grain from the River Prut to distribute up the Danube to central Europe or down through the Black Sea to Mediterranean and Atlantic ports. We gazed at the first houses of the port, built on low land that is flooded completely whenever it rains.

"How this makes me long for home! " exclaimed Sergei Nicholaivich in Russian. The streets of water had recalled his home town, the " little Venice" of Valcov near the sea. For him, I found, this was to be no ordinary voyage. Son of Lipovan fishermen for generations, he had been borne by the war as a soldier of sixteen out into an unfamiliar world. The disastrous campaigns which had raged back and forth over Romania, tearing up the deeply rooted lives of millions of shepherds, fishermen, and farmers, had left him adrift in Bucharest. First as a singer in a balalaika orchestra, then as an artist, he had struggled along with the tens of thousands of other provincials who threw in their lot with Romania's rising postwar capital.

But city life was not for him. Despite twenty years of it, there was something stronger. Now he was going back to the fisherman 's life to which he had been born. "Many Russians have died of homesickness,'' he said. "And many who have died have requested that a bit of earth from their native land be buried with them so they would not feel so far from the home they love."

Now in Bucharest I had heard of the vast and mysterious land of the Danube Delta, and when spring came I procured from the military authorities the necessary special permit to pass through the Delta zone to Valcov in Bessarabia on the Black Sea. But my bicycle, on which I had pedaled from Krakow all the way through Poland and Romania, had to be left behind: there are no railways nor, at the time of my visit, were there any feasible roads in the Delta; and so my destination could best be reached by water.

On the "Romania Mare", which I boarded at Oltenita, I met Sergei Nicholaivich, a Valcov Russian. Silistra fell behind us ; then the big railway bridge at Cernavoda, the only bridge to cross the Danube in its lower stretches. Here the sea is only 30 miles away and a canal has long been under consideration, for the river, instead of following its logical outlet, makes a sudden turn to the north and wanders on for more than 200 miles. Vivid scenes succeeded each other: the river traffic, the little ports, the wide brown reach of water, the green marshlands.

After passing a few fields of grain and a rare herd of cows wading under willows growing in the water out from the muddy shore, the Romania Mare came into Galati. Romanian, German, and Greek boats lay at the docks loading lumber and grain from the River Prut to distribute up the Danube to central Europe or down through the Black Sea to Mediterranean and Atlantic ports. We gazed at the first houses of the port, built on low land that is flooded completely whenever it rains.

"How this makes me long for home! " exclaimed Sergei Nicholaivich in Russian. The streets of water had recalled his home town, the " little Venice" of Valcov near the sea. For him, I found, this was to be no ordinary voyage. Son of Lipovan fishermen for generations, he had been borne by the war as a soldier of sixteen out into an unfamiliar world. The disastrous campaigns which had raged back and forth over Romania, tearing up the deeply rooted lives of millions of shepherds, fishermen, and farmers, had left him adrift in Bucharest. First as a singer in a balalaika orchestra, then as an artist, he had struggled along with the tens of thousands of other provincials who threw in their lot with Romania's rising postwar capital.

But city life was not for him. Despite twenty years of it, there was something stronger. Now he was going back to the fisherman 's life to which he had been born. "Many Russians have died of homesickness,'' he said. "And many who have died have requested that a bit of earth from their native land be buried with them so they would not feel so far from the home they love."

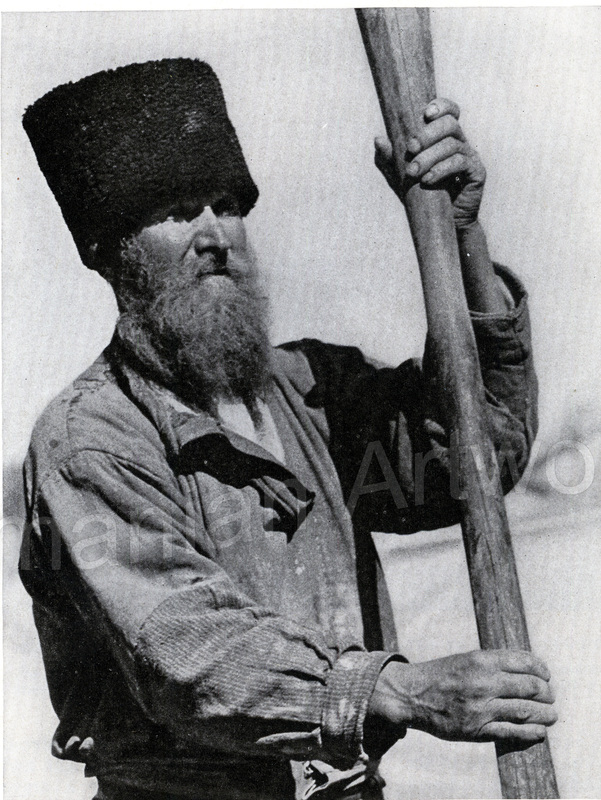

The fare is simple: fish and fish soup, eaten with wooden spoons from a bowl in the center of the table, and sour black bread baked in clay ovens shaped like the little houses which stand in many Valcov gardens. Traditionally, the Lipovan wears a long, full beard, but nowadays unmarried youths often are clean-shaven.

Near Tulcea the Danube splits into three big branches which flow through the wilderness of the Delta. The middle one, with Sulina as its Black Sea port, is the only one safe for larger ships, and along it passes all the through river navigation. Surprisingly enough, 67 per cent of the Danube's total volume flows out the Chilia Arm, the northernmost channel. Yet only a small line of boats goes down it, back and forth to Valcov, transporting the fish and more especially the caviar for which the place is famous. Thus Valcov lies far off the usual lines of communication. As a part of Bessarabia, which borders on the Soviet Union, Valcov was Russian from 1878 to 1918. Now it again belongs to Romania.

Age-old customs, however, have altered little. Indeed, this whole coastal region has been the scene of succeeding settlements of remote peoples and races as changing as the course of the river itself. A hundred miles to the south is Constanta, whose name of Tomis, where Ovid was exiled, was forgotten during the long centuries of the Turkish Empire, Russia's great rival on the Black Sea.

For years Tsar and Sultan contended for the Delta. South of the river, along the coast to Constanta, are villages of Romanians, Tatars, Bulgars, Germans, and Turks. When we stopped at the port of Tulcea, I saw the slim minarets one finds throughout the Balkan lands where the Ottoman Empire left its indelible stamp. Then in Ismail, on the northern side of the Delta, I saw the bulbous red steeples of the Russian Orthodox churches. Here was the territory marking the limits of the Russian Slav advance coming down from the north and arrested by the formidable waste of changing waterways and the thousand square miles of marshlands the river deposited at its mouth. Ismail was for a time, however, a very strong Turkish fortress. It was stormed and sacked in 1 790 by the Russian General Alexander Vasilievich Suvarov, who foughtincredible battles against the armies of the Crescent in this seemingly sunken continent of greenery aswarm with water fowl and amphibia and flanked on the north and south by the barren coasts of the stormy Black Sea.

Age-old customs, however, have altered little. Indeed, this whole coastal region has been the scene of succeeding settlements of remote peoples and races as changing as the course of the river itself. A hundred miles to the south is Constanta, whose name of Tomis, where Ovid was exiled, was forgotten during the long centuries of the Turkish Empire, Russia's great rival on the Black Sea.

For years Tsar and Sultan contended for the Delta. South of the river, along the coast to Constanta, are villages of Romanians, Tatars, Bulgars, Germans, and Turks. When we stopped at the port of Tulcea, I saw the slim minarets one finds throughout the Balkan lands where the Ottoman Empire left its indelible stamp. Then in Ismail, on the northern side of the Delta, I saw the bulbous red steeples of the Russian Orthodox churches. Here was the territory marking the limits of the Russian Slav advance coming down from the north and arrested by the formidable waste of changing waterways and the thousand square miles of marshlands the river deposited at its mouth. Ismail was for a time, however, a very strong Turkish fortress. It was stormed and sacked in 1 790 by the Russian General Alexander Vasilievich Suvarov, who foughtincredible battles against the armies of the Crescent in this seemingly sunken continent of greenery aswarm with water fowl and amphibia and flanked on the north and south by the barren coasts of the stormy Black Sea.

The "Romania Mare" twisted through treacherous flats intersected by a maze of channels which looked exactly alike to everyone except the pilot. Then, with a final twirl of the wheel, our little ship was turned to bring us head on against the current to the Valcov dock. The pier was stacked with crates and barrels and thronged with interested villagers. At one side stood a barefooted man with a huge beard that covered the front of his white linen smock. Sergei recognized him as his brother. They embraced, kissing each other three times on the cheek. The brother, whom Sergei introduced as Vasili, held himself very straight and met our curious glances with a grave serenity.

'See what a man!" Sergei Nicholaivich turned to me proudly. " So I would have been had I never seen the city." "And you?" he asked me. "What will you do? You must come to my mother's." I looked around: no hotels, no porters, no carriages. Waterways and canals stretched in every direction. Under a wooden bridge a row of black high-prowed fishing boats was drawn up along the miry bank. In one of these workaday gondolas Sergei's brother rowed us through the main canal and then, turning into one of the "side streets," poled us along in a network of narrow waterways just wide enough for two boats to slide past each other. They were bordered by woven fences, behind which I caught glimpses of straight-stalked hollyhocks and lupines and the fishermen 's deep-eaved houses. Willow trees drooped over the water. Gliding under the slanting sun of this warm May afternoon, it seemed that I was drifting through a mirror like Alice into Wonderland.

'See what a man!" Sergei Nicholaivich turned to me proudly. " So I would have been had I never seen the city." "And you?" he asked me. "What will you do? You must come to my mother's." I looked around: no hotels, no porters, no carriages. Waterways and canals stretched in every direction. Under a wooden bridge a row of black high-prowed fishing boats was drawn up along the miry bank. In one of these workaday gondolas Sergei's brother rowed us through the main canal and then, turning into one of the "side streets," poled us along in a network of narrow waterways just wide enough for two boats to slide past each other. They were bordered by woven fences, behind which I caught glimpses of straight-stalked hollyhocks and lupines and the fishermen 's deep-eaved houses. Willow trees drooped over the water. Gliding under the slanting sun of this warm May afternoon, it seemed that I was drifting through a mirror like Alice into Wonderland.

Men with long hair and beards padded barefoot along rickety little wooden sidewalks raised on stilts from the water. Their gaze was clear and blue-eyed, at once childlike and spiritual. Crowding over, they let by a woman carrying buckets of water on a wooden shoulder yoke.

Two shawled women poled past in a boat with a load of glistening river mud. I looked questioningly at Sergei Nicholaivich. "Mud from the river bottom is used to build and repair our houses," he explained. " Dried, it is as hard as clay. Whenever cracks appear in the walls, all we do is plaster wet mud over them , until you 'd think the house had measles. Then the daubs are whitewashed and the house is as good as new.

"The women take care of all of this," he added, "and every Saturday they whitewash most of the house inside and out."

Our boat drew up in a tiny inlet which took the place of a private entrance in this

woodland Venice. Through the gate of the willow fence we walked into a vegetable garden, coming to a low house the color of baked mud, with roses in a tangle against its sides. We stepped over the threshold into a long room divided by an enormous clay stove. A shelf of glazed pottery circled the walls. Here Sergei's family had gathered, waiting to receive him.

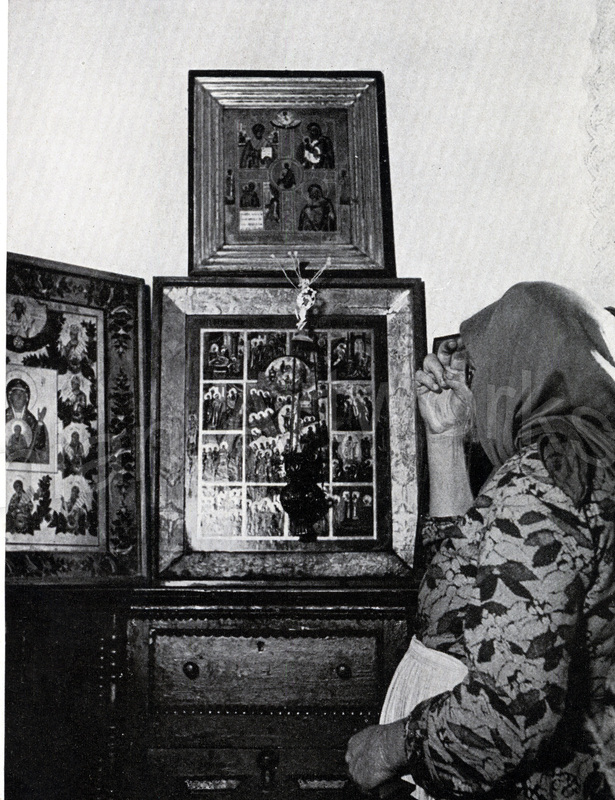

When he entered, everyone from the little children up made a deep bow, the women bowing even lower than the men. Sergei Nicholaivich walked straight to the family icon which is always in the far corner at the right of the entrance door. Bending low, he made a majestic sign of the cross. His hand, touching the forehead, swept nearly to the floor, then from the right shoulder over to the left. These reverences he repeated three times, after which he went from one to the other, beginning with the old men, and each kissed him thrice on the cheek. Throughout the entire ritual of welcome to the home-coming son there was an impressive silence. I had the feeling that these were decidedly more than ordinary fisherfolk.

Two shawled women poled past in a boat with a load of glistening river mud. I looked questioningly at Sergei Nicholaivich. "Mud from the river bottom is used to build and repair our houses," he explained. " Dried, it is as hard as clay. Whenever cracks appear in the walls, all we do is plaster wet mud over them , until you 'd think the house had measles. Then the daubs are whitewashed and the house is as good as new.

"The women take care of all of this," he added, "and every Saturday they whitewash most of the house inside and out."

Our boat drew up in a tiny inlet which took the place of a private entrance in this

woodland Venice. Through the gate of the willow fence we walked into a vegetable garden, coming to a low house the color of baked mud, with roses in a tangle against its sides. We stepped over the threshold into a long room divided by an enormous clay stove. A shelf of glazed pottery circled the walls. Here Sergei's family had gathered, waiting to receive him.

When he entered, everyone from the little children up made a deep bow, the women bowing even lower than the men. Sergei Nicholaivich walked straight to the family icon which is always in the far corner at the right of the entrance door. Bending low, he made a majestic sign of the cross. His hand, touching the forehead, swept nearly to the floor, then from the right shoulder over to the left. These reverences he repeated three times, after which he went from one to the other, beginning with the old men, and each kissed him thrice on the cheek. Throughout the entire ritual of welcome to the home-coming son there was an impressive silence. I had the feeling that these were decidedly more than ordinary fisherfolk.

Bessarabia belonged to Romania until 1812 , when it was taken by Russia, but after the World War it again became part of Romania. The Soviet Union now looks longingly at this rich granary, which they still consider "occupied territory." Flowing across Europe from Germany, the muddy Danube empties into the Black Sea through a many-mouthed delta.

"Ours is a puritan race," said Sergei Nicholaivich to me afterward. "Whatever befalls us, whether it brings joy or sorrow, we must accept serenely. "How did our people come to live in these lost marshlands of the Delta? You see, at the time of

Tsar Alexis, the father of Peter the Great, the priests under the Patriarch Nikon decided to make a new translation from the Greek of the Bible and the Books of the Service. "Of course they found things in the old translation which they thought were wrong and which they corrected. But many of the Russians couldn't see why they should change what they had been saying and doing for 500 years. This was the beginning of the division of the Church.

"There were really no great differences at first. Only such things as, for example, the Orthodox making the cross with three fingers, representing the Trinity. We Lipovans claim that the Trinity is the thumb and last two fingers, and we make the cross with the two middle fingers, saying that in all of the pictures Christ gives the benediction with these two. "But then Tsar Alexis' son, Peter, wanted to break all the old customs and to Europeanize Russia. He was the first Tsar to ·visit far-western Europe, and he cut the beards of the boyars and introduced the smoking of tobacco.

"He wished to build a fleet to defeat the Swedes. So he went himself to Holland and England to see how to make ships. He came back after working there as a simple laborer for half a year, and wanted to change everything. Part of the Russians said he wasn't their Tsar Batyushka, their Little Father, but an Antichrist.

Tsar Alexis, the father of Peter the Great, the priests under the Patriarch Nikon decided to make a new translation from the Greek of the Bible and the Books of the Service. "Of course they found things in the old translation which they thought were wrong and which they corrected. But many of the Russians couldn't see why they should change what they had been saying and doing for 500 years. This was the beginning of the division of the Church.

"There were really no great differences at first. Only such things as, for example, the Orthodox making the cross with three fingers, representing the Trinity. We Lipovans claim that the Trinity is the thumb and last two fingers, and we make the cross with the two middle fingers, saying that in all of the pictures Christ gives the benediction with these two. "But then Tsar Alexis' son, Peter, wanted to break all the old customs and to Europeanize Russia. He was the first Tsar to ·visit far-western Europe, and he cut the beards of the boyars and introduced the smoking of tobacco.

"He wished to build a fleet to defeat the Swedes. So he went himself to Holland and England to see how to make ships. He came back after working there as a simple laborer for half a year, and wanted to change everything. Part of the Russians said he wasn't their Tsar Batyushka, their Little Father, but an Antichrist.

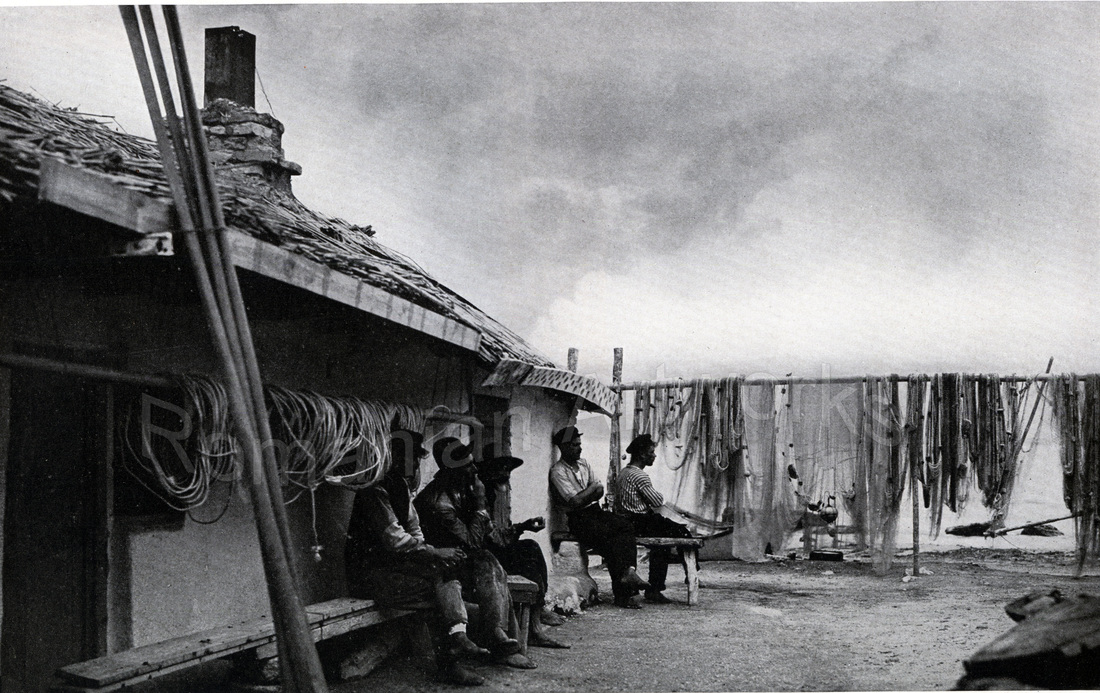

Fishing from small boats where the river current meets the Black Sea is hazardous, for the storms in this area sweep off the steppes with fierce and sudden fury . Thatched roofs are often blown away. Even the chimneys are damaged, as on this shack where toppled stones have been replaced with a pipe. In many huts fishermen sleep on flat stoves during bitter winter nights.

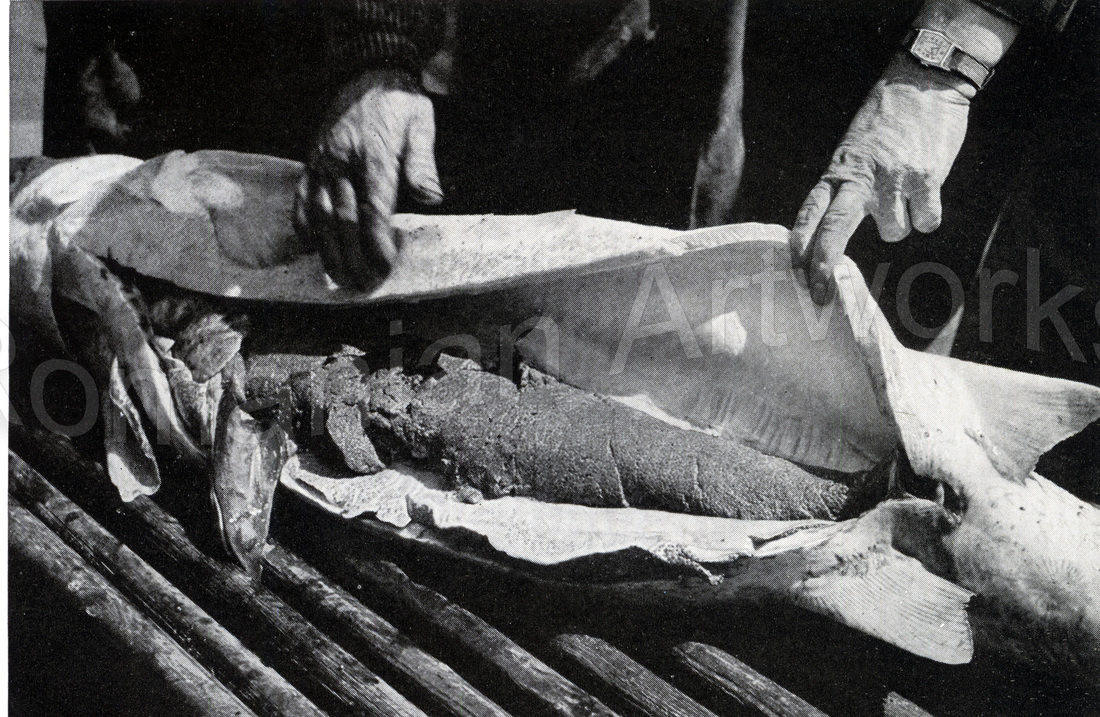

While the oarsman controls the boat (a lotka) , two men haul the prize alongside with gaffs. Even after the fish is taken aboard, it may thresh about viciously until killed. Over the gunwale a fourth man pulls in the rig of bare hooks strung on short cords. Sturgeon, heading inshore against the fresh-water current, swim into the hooks.

After the roe is removed, it is strained through a sieve to clean it of fibrous tissues. The eggs are then washed, treated with salt, and packed in cans or barrels as caviar. Romanians regard caviar as a staple part of their diet. They serve it with seasoning in a large bowl, with crackers and toast , as canapes with thin slices of cheese and vodka, and in many other ways.

"Peter cut his beard, smoked, and instead of the traditional greatcoat of the boyars edged with beaver or sable fur and trimmed with rows of pearls and diamonds, he decreed the new-type caftan, thus changing the national costume. His son Alexis was for the old ways, so the boyars and the people found in him the center of their hopes, but his father had him put to death.

"The Old Believers were seeking refuge in the wild country. A sect in the mountains, believing the Antichrist had come in the Tsar, proclaimed the Judgment Day was at hand. They burned all the churches with themselves inside. There was a great wave of hysteria. Peter the Great began sending the police to fight with the people, the majority of whom had fallen under the influence of fanatics. These believers were obliged to flee farther and farther. Some went north into Siberia, some into the Caucasus. And others, escaping first into the linden forests from which they got their name of Lipovan-'lipa' is Russian for 'linden tree'-finally came here, to the Delta, which was then under Turkish suzerainty and could be reached only by sea.

"The marshlands and the thousands of islands were deserted and here our ancestors stayed, naming their settlement 'Vilkov,' from the Russian vilka, meaning ' fork,' after the three channels to the sea. They made a few canals and with the dirt from them created ground high enough for their houses.

"They continued wearing their beards long, like the old boyars, and refused to take up smoking or to make any other changes in the old customs."

"The Old Believers were seeking refuge in the wild country. A sect in the mountains, believing the Antichrist had come in the Tsar, proclaimed the Judgment Day was at hand. They burned all the churches with themselves inside. There was a great wave of hysteria. Peter the Great began sending the police to fight with the people, the majority of whom had fallen under the influence of fanatics. These believers were obliged to flee farther and farther. Some went north into Siberia, some into the Caucasus. And others, escaping first into the linden forests from which they got their name of Lipovan-'lipa' is Russian for 'linden tree'-finally came here, to the Delta, which was then under Turkish suzerainty and could be reached only by sea.

"The marshlands and the thousands of islands were deserted and here our ancestors stayed, naming their settlement 'Vilkov,' from the Russian vilka, meaning ' fork,' after the three channels to the sea. They made a few canals and with the dirt from them created ground high enough for their houses.

"They continued wearing their beards long, like the old boyars, and refused to take up smoking or to make any other changes in the old customs."

After the first solemnities of Sergei Nicholaivich 's reception, we all sat down on benches at a huge bare table beneath the icon in the "Holy Corner." Beside each place lay a wooden spoon, deeply cupped and satin-smooth with wear. First came boiled fish and then a clear fish soup with a bit of potato in it. (Unless the soup contains something solid, it always comes after the fish dish.) With this, instead of bread we ate pirozhki, a black flour pastry filled with cabbage. Following the example of the bearded old men, we let this part of the meal pass almost in silence. But then, to celebrate, there were big fresh strawberries served with smetana, or sour cream. The fire in the heavy iron samovar was replenished with coals from the kitchen, and glass after glass of steaming tea passed around.

Sergei Nicholaivich's mother impulsively leaned over and put an extra blob of the rich cream on his berries, then blushed protestingly as a roar of laughter broke out. Embarrassed, Sergei turned to translate their joking remarks for me.

"Children love smetana. So when one is an only or a spoiled child and his mother

is always putting it on everything he eats, he is known as a 'smetanik.' That's what

they are calling me.

"Now they are telling me about two storks and a duck." Sergei kept me informed while keeping his eyes on the others who were talking, each one supplementing, confirming, or encouraging the others. "They say that a duck laid an egg in a stork's nest on the chimney of a house. A committee of storks gathered on the roof. They judged that something was not quite right in this whole business and killed the mamma stork, the duck, and destroyed the nest.

"We know that the storks in their conjugal relations are very strict,'' he explained. "They come back to the same nest year after year, and always the same couple. When they arrive, we know that winter is over and spring on its way. Every house must have its nest on the roof, for the storks bring luck to the family"

Sergei Nicholaivich's mother impulsively leaned over and put an extra blob of the rich cream on his berries, then blushed protestingly as a roar of laughter broke out. Embarrassed, Sergei turned to translate their joking remarks for me.

"Children love smetana. So when one is an only or a spoiled child and his mother

is always putting it on everything he eats, he is known as a 'smetanik.' That's what

they are calling me.

"Now they are telling me about two storks and a duck." Sergei kept me informed while keeping his eyes on the others who were talking, each one supplementing, confirming, or encouraging the others. "They say that a duck laid an egg in a stork's nest on the chimney of a house. A committee of storks gathered on the roof. They judged that something was not quite right in this whole business and killed the mamma stork, the duck, and destroyed the nest.

"We know that the storks in their conjugal relations are very strict,'' he explained. "They come back to the same nest year after year, and always the same couple. When they arrive, we know that winter is over and spring on its way. Every house must have its nest on the roof, for the storks bring luck to the family"

Boxes of caviar, sturgeon, and herring are piled awaiting shipment from the sheds of the Cooperative, which controls the fisheries of the region. Fishermen are paid set prices for each kilogram (2.2 pounds) of fresh or salted fish. Valcov still lives in the age of wood: boats, bridges, many of the buildings, sidewalks, house furnishings, fences, and wharves are fashioned of lumber.

Black Sea sturgeon, seeking spawning grounds, swim up the fresh-water streams veining the marshlands of the Danube Delta. Fences across the channels are closed behind the ascending fish. Trapped, they are easily netted or gaffed in the shallow waters. During the busy fishing season, the men live in these crude encampments, returning to Valcov only for supplies.

But the great topic for every one was the disaster which had befallen Valcov that winter. In winter months the cruel and bitter northeast winds blow down from the steppes across the Black Sea. "Sometimes the Danube freezes over in one night," said Sergei Nicholaivich. "Ships are caught in midstream and may remain in the grip of the ice until spring.

"This last winter the river froze over. When spring came the river was jammed with pack ice and swollen with rain. It rained and rained. The river rose day after day, week after week, until the whole of Valcov was under water.

In this disaster Sergei's family lost its oldest member. He died from exposure during one of the terrible nights spent in the open boats. The clay house had been destroyed by the water. "Our winters ... brr! " shivered Sergei. "The withe fences keep some of the cold wind off, and layers of rushes are piled around the house walls like a winter overcoat. But even then it's unbearable."

He laughed. "They used to tell me when I was small that if I were good it would snow sugar. And if it was snowing on Christmas Day, that meant Saint Nicholas was shaking his white beard over our house."

Eleven of the family had sat down at the table. When we stood up, and everyone had crossed himself again three times, the old mother herself took me into the room where I was to sleep. Native tapestries in Bessarabian horizontal leaf patterns hung around the walls, and at the foot of the bed was a wooden chest ornamented with painted flowers. What held my eye was a stack of pillows on it, beginning with a huge pillow at the bottom and pyramiding to a tiny one on top, all of them to tuck around one on freezing winter nights. When I was comfortable, the old mother and the granddaughter who had helped her left me, after making a low bow. I learned afterward that the Lipovans consider a guest in their home as one "sent by God." I was awakened by cathedral bells. When I came out of my room the whole family had already gathered, and with an earlymorning mist still hanging over the water we rowed to Sunday Mass. A trembling image reflected on the water was our first glimpse of the great white cathedral. Though built on a sand patch and screened by trees, it would seem very European and cosmopolitan were it not that its domes and towers are topped by big onion-shaped cupolas which rise like fanciful turbans in the sky. Starchy pinafored girls, men with cheeks scrubbed, women whose hair was brushed shiny under their head shawls-they were all there, coming afoot over the wooden bridges, or by boats that jostled one another on their way.

"This last winter the river froze over. When spring came the river was jammed with pack ice and swollen with rain. It rained and rained. The river rose day after day, week after week, until the whole of Valcov was under water.

In this disaster Sergei's family lost its oldest member. He died from exposure during one of the terrible nights spent in the open boats. The clay house had been destroyed by the water. "Our winters ... brr! " shivered Sergei. "The withe fences keep some of the cold wind off, and layers of rushes are piled around the house walls like a winter overcoat. But even then it's unbearable."

He laughed. "They used to tell me when I was small that if I were good it would snow sugar. And if it was snowing on Christmas Day, that meant Saint Nicholas was shaking his white beard over our house."

Eleven of the family had sat down at the table. When we stood up, and everyone had crossed himself again three times, the old mother herself took me into the room where I was to sleep. Native tapestries in Bessarabian horizontal leaf patterns hung around the walls, and at the foot of the bed was a wooden chest ornamented with painted flowers. What held my eye was a stack of pillows on it, beginning with a huge pillow at the bottom and pyramiding to a tiny one on top, all of them to tuck around one on freezing winter nights. When I was comfortable, the old mother and the granddaughter who had helped her left me, after making a low bow. I learned afterward that the Lipovans consider a guest in their home as one "sent by God." I was awakened by cathedral bells. When I came out of my room the whole family had already gathered, and with an earlymorning mist still hanging over the water we rowed to Sunday Mass. A trembling image reflected on the water was our first glimpse of the great white cathedral. Though built on a sand patch and screened by trees, it would seem very European and cosmopolitan were it not that its domes and towers are topped by big onion-shaped cupolas which rise like fanciful turbans in the sky. Starchy pinafored girls, men with cheeks scrubbed, women whose hair was brushed shiny under their head shawls-they were all there, coming afoot over the wooden bridges, or by boats that jostled one another on their way.

The bells were still ringing, the sound rippling over the placid air. One of them, the huge bell in the tower, was cast in 1877 , I was told, in commemoration of the delivery of the Delta region from the Turks. Inside, a choir was singing the incredibly mystic and lovely chorals of the Orthodox litany, the voices swelling sometimes to a tremendous volume, then dying to sustained pianissimos. During the Mass celebrated by the priests in rich brocaded robes, one worshiper prostrated himself completely, lying with his arms outstretched. Others, humbled on their knees, touched their foreheads repeatedly to the floor in token that they gave themselves wholly to their God. All the magnificent voices of the Russians were not in the choir. In the teahouse I heard groups of young men singing in perfect harmony; and later I heard the men, as they pulled their boats, sing ancient boatmen's songs from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

As we poled back through the flowery willow-drooped canals, two little girls tossed roses and forget-me-nots into the boat from a frail bridge overhead. And farther along another child shyly offered us a penny's worth of the dried strawberry leaves which the Lipovans use to make a fragrant tea.

Our boat was tied in a long row with dozens of others-all exactly alike except for the number painted on the front to identify them easily for official control and we stepped out on the one terra firma promenade, which was crowded with Sunday strollers. Remarking on the animation among the youthful, not without its purport, I was told the young men get married at about 21, usually directly after military service, and the girls marry earlier, most often at 16. The young girls are allowed to walk on the promenade across the bridges, but not to dance except at weddings. As a result of this restriction, at some of the teahouses where tables and chairs were set in the open and music from a balalaika or guitar invited the customers to dance, it was the boys and young men who performed the intricate figures and flying steps of the Cossatchok, while shawled women and fair-haired girls looked on.

We sat down in one of these fishermen 's teahouses where tea costs five lei (three and a half cents) the service. Atop a china pot holding about six glasses of hot water rests a tiny pot of strong tea which keeps hot in the steam from below. With this are served four pieces of sugar and a slice of lemon. The proper way to drink is out of the saucer. In the cold this has the advantage that the steam from the scalding tea warms the face. The saucer is balanced on the first three fingers of the left hand. Between the other two fingers and the palm is placed loaf sugar broken into small bits. (Granulated sugar is never used.) One nibbles a bit of the sugar, then takes a sip, noisily, of tea. When you 've had enough, you turn the glass upside down on the saucer and put any leftover sugar on top. "In the old days, when sugar was a luxury,'' Sergei told me, "a lump was tied to a string from the ceiling. Each one would take a sip of tea and a lick of the sugar and then let it swing over to the next person. This was called the licking way of taking tea."

Tea drinking in quantities has the effects of a Turkish bath. So a part of the ritual

is putting a napkin over the back of the neck with the ends hanging down in front so that after many glasses one can wipe away the perspiration to keep it from streaming down the face.

Discussing the amenities of tea drinking, we watched a youth who was dancing. He was patched like a thrifty harlequin, and his smock flapped with each bend of the knees. Sergei Nicholaivich pointed out to me that the Lipovans and Orthodox Russians of Valcov have no other national dress than the smock and tight trousers one occasionally sees. "There are other Russian sectarians in Galati, Iasi, and Bucharest who wear distinctive dress," he said. "They belong to the group called Scopiti (Skoptsi) , whom you have seen in Bucharest as the droshky drivers wearing high astrakhan hats and long full caftan coats of black velvet with colored sashes. Coming sometimes from the higher classes, they were exiled from Russia even before the war. "Valcov has some 8,000 inhabitants. The majority are Lipovans, the remainder being Orthodox Russians, a few Romanian officials, and some Jewish families.

As we poled back through the flowery willow-drooped canals, two little girls tossed roses and forget-me-nots into the boat from a frail bridge overhead. And farther along another child shyly offered us a penny's worth of the dried strawberry leaves which the Lipovans use to make a fragrant tea.

Our boat was tied in a long row with dozens of others-all exactly alike except for the number painted on the front to identify them easily for official control and we stepped out on the one terra firma promenade, which was crowded with Sunday strollers. Remarking on the animation among the youthful, not without its purport, I was told the young men get married at about 21, usually directly after military service, and the girls marry earlier, most often at 16. The young girls are allowed to walk on the promenade across the bridges, but not to dance except at weddings. As a result of this restriction, at some of the teahouses where tables and chairs were set in the open and music from a balalaika or guitar invited the customers to dance, it was the boys and young men who performed the intricate figures and flying steps of the Cossatchok, while shawled women and fair-haired girls looked on.

We sat down in one of these fishermen 's teahouses where tea costs five lei (three and a half cents) the service. Atop a china pot holding about six glasses of hot water rests a tiny pot of strong tea which keeps hot in the steam from below. With this are served four pieces of sugar and a slice of lemon. The proper way to drink is out of the saucer. In the cold this has the advantage that the steam from the scalding tea warms the face. The saucer is balanced on the first three fingers of the left hand. Between the other two fingers and the palm is placed loaf sugar broken into small bits. (Granulated sugar is never used.) One nibbles a bit of the sugar, then takes a sip, noisily, of tea. When you 've had enough, you turn the glass upside down on the saucer and put any leftover sugar on top. "In the old days, when sugar was a luxury,'' Sergei told me, "a lump was tied to a string from the ceiling. Each one would take a sip of tea and a lick of the sugar and then let it swing over to the next person. This was called the licking way of taking tea."

Tea drinking in quantities has the effects of a Turkish bath. So a part of the ritual

is putting a napkin over the back of the neck with the ends hanging down in front so that after many glasses one can wipe away the perspiration to keep it from streaming down the face.

Discussing the amenities of tea drinking, we watched a youth who was dancing. He was patched like a thrifty harlequin, and his smock flapped with each bend of the knees. Sergei Nicholaivich pointed out to me that the Lipovans and Orthodox Russians of Valcov have no other national dress than the smock and tight trousers one occasionally sees. "There are other Russian sectarians in Galati, Iasi, and Bucharest who wear distinctive dress," he said. "They belong to the group called Scopiti (Skoptsi) , whom you have seen in Bucharest as the droshky drivers wearing high astrakhan hats and long full caftan coats of black velvet with colored sashes. Coming sometimes from the higher classes, they were exiled from Russia even before the war. "Valcov has some 8,000 inhabitants. The majority are Lipovans, the remainder being Orthodox Russians, a few Romanian officials, and some Jewish families.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed